Basics of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

The Basics of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

What is Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis?

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a lung disease that causes scar tissue to build up in the lungs. Scar tissue makes the lungs stiff and not very flexible. This causes symptoms, such as fatigue (tiredness not relieved by sleeping), breathlessness, and nagging, dry cough. IPF is progressive, which means that it tends to get worse over time.

What causes IPF?

Doctors do not have a firm answer to this question. In fact, the name of the condition itself shows this:

- Idiopathic is medical language for “cause is unknown”

- Pulmonary means “having to do with the lungs”

- Fibrosis means “too much scar tissue”

So, IPF means “too much scar tissue in the lungs with an unknown cause”.

There are many medical researchers who are working to try to understand what might cause IPF. The theory that has the most data to support it is called the improper wound healing theory.1,2

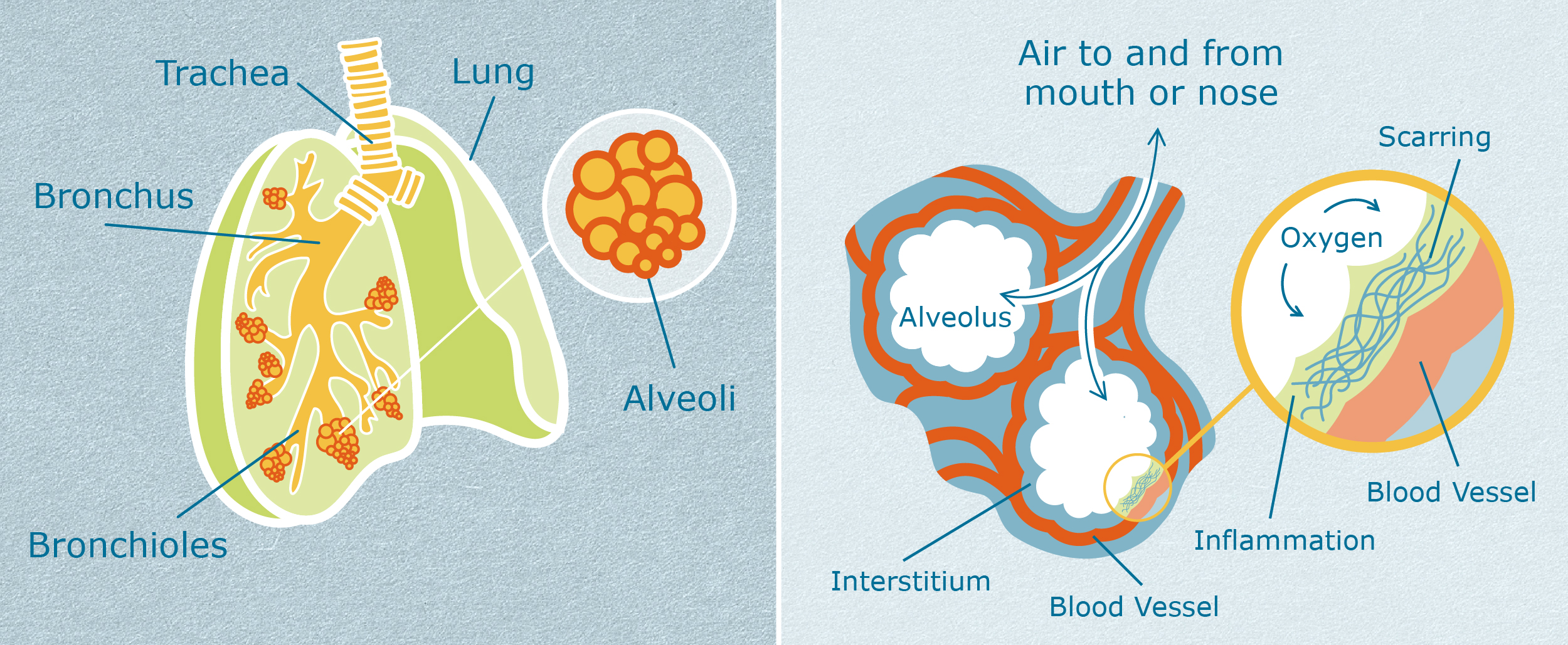

Lungs are made of cells, just like every part of the human body is made of cells. The delicate, air sacs in the lungs are called alveoli (al-VEE-oh-lie), and they are particularly easy to hurt. The cells in the alveoli can be wounded or damaged by many things. These include:

- Smoking

- Inhaling irritating chemicals or fumes, especially if it happens frequently

- Viral or bacterial infections

- Inhaling stomach acid frequently, which can happen in gastroesophageal reflux disease

When alveoli are wounded, these air sacs no longer work well to transport oxygen into the blood stream and carbon dioxide out of the bloodstream.

In healthy people without IPF, injured cells in alveoli are healed through a complex process of many steps.3 A summary of these steps is as follows:

- The cells of the immune system respond. Immune cells move through the blood to the damaged alveoli.

- The immune system cells begin to clear away the infection or damaging substances. Sometimes the immune system cells have to kill even more cells in the alveoli. This can happen because the alveoli cells are infected with viruses or bacteria, or perhaps they are much too damaged to repair.

- Scar tissue cells, called fibroblasts, move toward the wounded areas and make small “scabs” to cover the wounds.

- Healthy lung cells move toward the scabbed areas. They begin to grow and divide to make new healthy cells.

- The new healthy cells replace the damaged cells.

- As healthy cells are replacing damaged cells, the scar tissue cells (fibroblasts) self-destruct on purpose. The body no longer needs the small “scabs”.

- The body absorbs the dead fibroblasts, leaving new, healthy lung tissue behind.

In a person with IPF, something goes wrong with this process. It is thought that too much scar tissue forms, and then keeps on forming. The body never moves into the part of the process where fibroblasts (scar tissue cells) self-destruct on purpose, and healthy cells replace them. Unfortunately, for people with IPF, more and more scar tissue builds up in the lungs over time.

Did I do something to cause me to get IPF?

No, not directly.

There are certain things that raise the risk for IPF. These include smoking, working at a job that uses strong chemicals and fumes on a regular basis, having gastroesophageal reflux disease, or having an autoimmune disease like rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, or scleroderma. However, most people who do or experience these things do not get IPF.

IPF is not very common. According to the U.S. National Library of Medicine, about 100,000 people have IPF right now in the United States, and 30,000 to 40,000 people are newly diagnosed each year.4 Many more people than that have smoked or worked in a job that uses chemicals and fumes. Many more people than that have gastroesophageal reflux disease or an autoimmune disease. So, experiencing a risk factor does not mean that someone will definitely get IPF.

Also, some people who do get IPF have not experienced any of these risk factors. Doctors do not know why some people get IPF when they have not experienced any risk factors.

There does seem to be a genetic influence in IPF. That means that having certain versions of particular genes may make it more likely that a person will develop IPF after experiencing a risk factor. This is called a “genetic predisposition”. Having a genetic predisposition does not mean that a person will definitely get IPF if they experience a risk factor. It means they are more likely to get IPF if they experience a risk factor.

Sometimes IPF runs in families, and more than one family member has the condition. This is called “familial IPF”. Not everyone in such families will get IPF.

There are many unknowns about the genetic risk for getting IPF. Researchers are still working to understand these questions.4,5

Can IPF be treated?

Yes, but it cannot be cured with medication at this time.

IPF can be treated using certain medications that help slow down the buildup of scar tissue in the lungs. These medications do not cure the condition, and they do not seem to help with the symptoms of cough, fatigue, and breathlessness. Research studies suggest that people with IPF who take these medications have less lung damage over time. People with IPF who take the medications seem to have a better chance of living longer than those who do not.6

People with IPF are sometimes eligible for a lung transplant. While this cures the IPF, it replaces it with the difficulties and risks of having transplanted organs. This includes having to take very strong medications that suppress the immune system. These medications must be taken for life.

How long do I have to live?

No one can answer this question. The average life expectancy for a patient with IPF (counting from the time of diagnosis) is 3 to 5 years. But averages are tricky things. Some patients are quite sick when they are diagnosed, and they may live for only a few months. Some patients are diagnosed early. They can live for ten years, or even longer, especially if they take medications to slow down lung damage.7

It is impossible to predict at the time of diagnosis exactly how long any individual patient will live.

To improve the likelihood of longer survival, patients with IPF can:

- Seek care at a major, large hospital or clinic (tertiary center) with doctors who specialize in IPF

- Take their medications as their doctors prescribe them

- Stop smoking

- Participate in a pulmonary rehabilitation program, if recommended

- Keep all immunizations current according to doctor recommendations

- Seek structured support sources, such as support groups and individual therapy with a psychologist, counselor, or therapist.

References and further reading

- Wilson MS, Wynn TA. Pulmonary fibrosis: pathogenesis, etiology and regulation. Mucosal Immunol. 2009;2(2):103–121.

- Selman M, King TE, Pardo A; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society; American College of Chest Physicians. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: prevailing and evolving hypotheses about its pathogenesis and implications for therapy. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(2):136-51.

- Zemans RL, Henson PM, Henson JE, Janssen WJ. Conceptual approaches to lung injury and repair. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S9–S15.

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. Genetics Home Reference: Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Last updated June 11, 2019.

- National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD). Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Last updated 2017.

- Raghu G. Pharmacotherapy for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: current landscape and future potential. Eur Respir Rev. 2017;26(145).

- Guenther A, Krauss E, Tello S, et al. The European IPF registry (eurIPFreg): baseline characteristics and survival of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Res. 2018;19(1):141.