Overview of Project ECHO for ILD

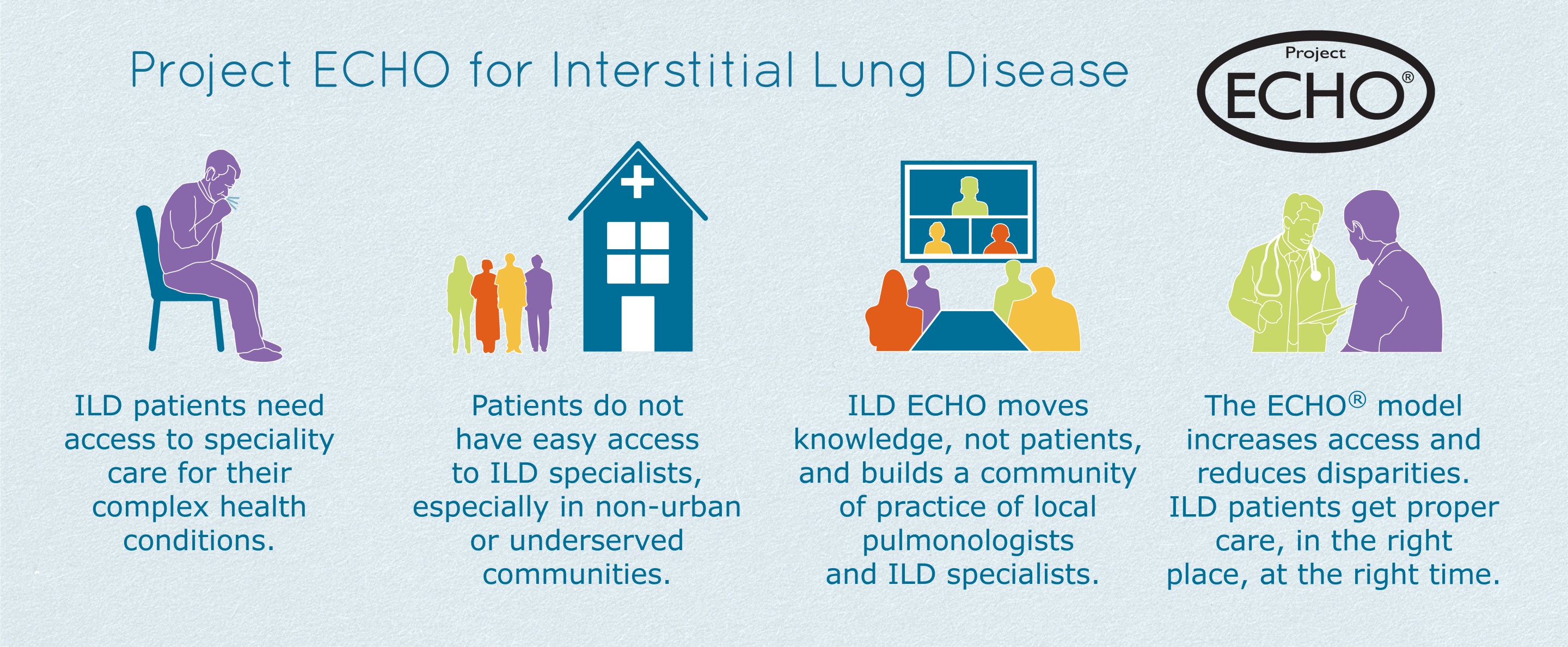

Project ECHO for Interstitial Lung Disease

“Advances in medical research and innovation mean little if they do not reach the patients who need them.”

— Struminger B, Arora S, et al., The Lancet. 2017

The U.S. healthcare system today is marked by significant healthcare disparities.1 This is especially true for those living in rural areas or in areas far from tertiary care centers due, in part, to a lack of access to specialty care providers.2 Indeed, it takes an average of 17 years for new medical knowledge to be well-integrated into patient care across settings.3

Busy, overbooked community providers are hard-pressed to manage their practices while keeping abreast of effective diagnostic and management guidelines, particularly in relatively uncommon disease fields or specialty areas of practice in which limited support and training are available.

Project ECHO is a movement whose mission is to demonopolize knowledge for community healthcare providers while democratizing access to best-practices of care for patients in underserved populations. The movement was originally designed by clinicians at the University of New Mexico to increase access to care for patients with hepatitis C infection in rural areas of the state. With this initial goal achieved, Project ECHO has grown to address disparity in healthcare access for patients with many types of conditions that are complex and require multidisciplinary management to achieve the best possible patient outcomes. Project ECHO is demonstrating every day that the right medical knowledge and expertise, in the right hands, at the right time, can save lives.

The ECHO Model

The ECHO “hub-and-spoke” model relies on videoconferencing to connect local providers across communities (spoke sites) with an interdisciplinary team of specialist providers at academic medical centers (hubs) during virtual “teleECHO” clinic sessions, which include brief educational lectures and de-identified case-based learning. The ECHO model is not telemedicine. Patients do not directly access specialist providers through videoconference or other means. Instead, it is a learning model where the community provider retains responsibility for their patient’s care and works with increasing independence as experienced is gained.

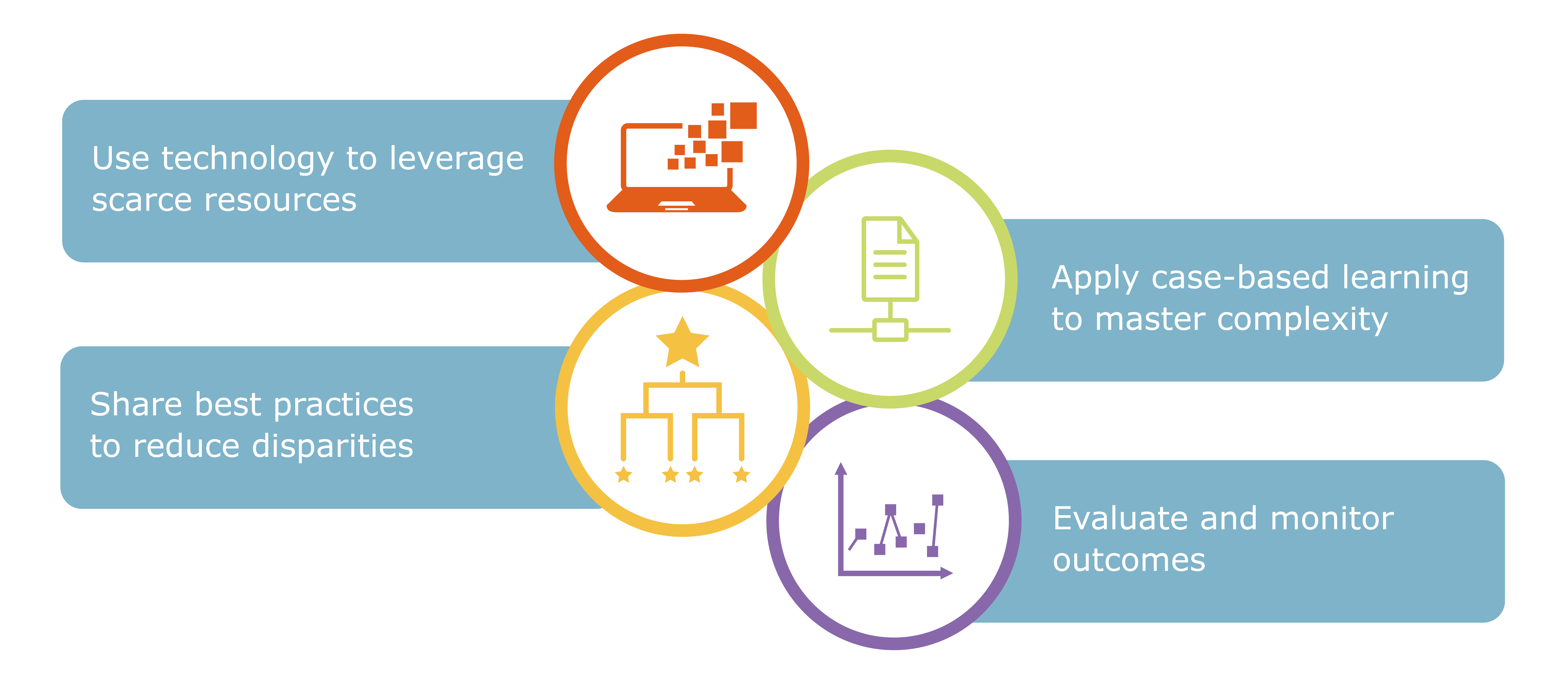

The ECHO model is built upon four principles:

- Use technology to AMPLIFY and leverage scarce resources;

- Share BEST PRACTICES to reduce disparities;

- Employ de-identified CASE-BASED LEARNING and guided practice to support participants in mastering complexity; and

- Monitor program outcomes using a web-based DATABASE.

Why launch Project ECHO for Interstitial Lung Disease (ILD)?

- ILDs are rare diseases, with a prevalence in the United States of 60 to 95 per 100,000.5,6 Community physicians and clinicians may encounter few such patients in practice.

- ILDs are highly challenging to identify and diagnose because most early symptoms are shared with many common diseases and conditions.

- A survey study7 of 600 patients with ILDs found:

- 55% reported one or more misdiagnoses, and 38% reported two or more misdiagnoses prior to the correct diagnosis.

- Among those who were initially misdiagnosed, the median time between the initial misdiagnosis and the final diagnosis was 11 months, with 34% reporting a delay of at least 2 years.

- The number of reported primary care visits before referral to a pulmonologist was one (27.8%), two (18.6%), three (18.6%), four (6.6%), and greater than four (23.8%).

- Unnecessary medications were commonly prescribed during the interval between initial medical consultation and the current diagnosis, including systemic corticosteroids (21.8%), antibiotics (32.0%), salmeterol/fluticasone (17.8%), N-acetylcysteine (13.5%), omeprazole (11.8%), and albuterol (11.6%).

- 61% reported undergoing an invasive diagnostic procedure, including 43.3% who had a surgical lung biopsy and 35.7% who had at least one bronchoscopy.

- Optimal ILD management requires a multidisciplinary team of pulmonologists, radiologists, pathologists, and primary care physicians. One study found that a tertiary team review led to a specific ILD diagnosis change in 53% of patients.8

- When surveyed before a recent ILD Collaborative educational activity9, community providers consistently reported a need for additional guidance to interpret evidence-based diagnostic criteria and management recommendations for ILDs.

- 61% could not correctly identify those criteria that would be inconsistent with usual interstitial pneumonia pattern on high-resolution CT scan.

- 61% could not correctly identify a treatment option that was strongly recommended by current clinical practice guidelines.

- 81% could not correctly quantify the treatment response associated with anti-fibrotic therapies in certain ILDs.

A national ILD ECHO network will provide local pulmonologists and primary care physicians across communities with the resources they have requested to feel confident in the diagnosis and personalized treatment of ILDs.

- The teleECHO clinic sessions will utilize technology for the secure exchange of medical health information and radiology imaging studies to optimally support a de-identified case-based learning model.

- The project will also establish a repository of de-identified clinical and imaging data to support medical education and clinical investigations in ILDs.

Benefits of participating in Project ECHO for ILD

- CME credit provided free of charge.

- Certification or accreditation with professional licensure and training organizations for completion of established curriculum.

- Opportunities for collaborative ILD research.

- Recognition as clinician with expertise in ILD diagnosis and management.

AMA Designation Statement

AMA Designation Statement

Project ECHO® designates this live activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 CreditTM. Physicians should claim only credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

References

- Healthy People 2020. Disparities. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

- The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About Rural Health.

- Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001.

- University of New Mexico. Project ECHO.

- Coultas DB, Zumwalt RE, Black WC, Sobonya RE. The epidemiology of interstitial lung diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150(4):967-972.

- Olson AL, Patnaik P, Hartmann N, et al. Prevalence and incidence of chronic fibrosing interstitial lung diseases with a progressive phenotype in the United States estimated in a large claims database analysis. Adv Ther. 2021;38(7):4100-4114. [Study sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim, the makers of Ofev®/nintedanib]

- Cosgrove GP, Bianchi P, Danese S. et al. Barriers to timely diagnosis of interstitial lung disease in the real world: the INTENSITY survey. BMC Pulm Med. 2018;18:9.

- Jo HE, Glaspole IN, Levin KC, et al. Clinical impact of the interstitial lung disease multidisciplinary service. Respirology. 2016;21(8):1438-1444.

- Pre-test outcomes data on file from an online educational activity entitled “Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Coordinating Care between Patients and Clinicians”, accredited by the Post Graduate Institute of Medicine and delivered by the ILD Collaborative in collaboration with the PlatformQ Health.