IPF and PF-ILD Clinical Trials

Experimental Pharmacologic Treatments for Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

and Progressive Fibrosing Interstitial Lung Disease

There are a number of pharmacologic (medication) treatments for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and progressive fibrosing interstitial lung disease (PF-ILD) that are still in stages of testing. These treatments are not approved to give to patients except as part of clinical trials. A clinical trial is a way for researchers to test a new medication or treatment in a small group of patients. Patients are watched carefully for side effects to make sure they do not suffer harm. If they do, the medication or treatment being tested is stopped.

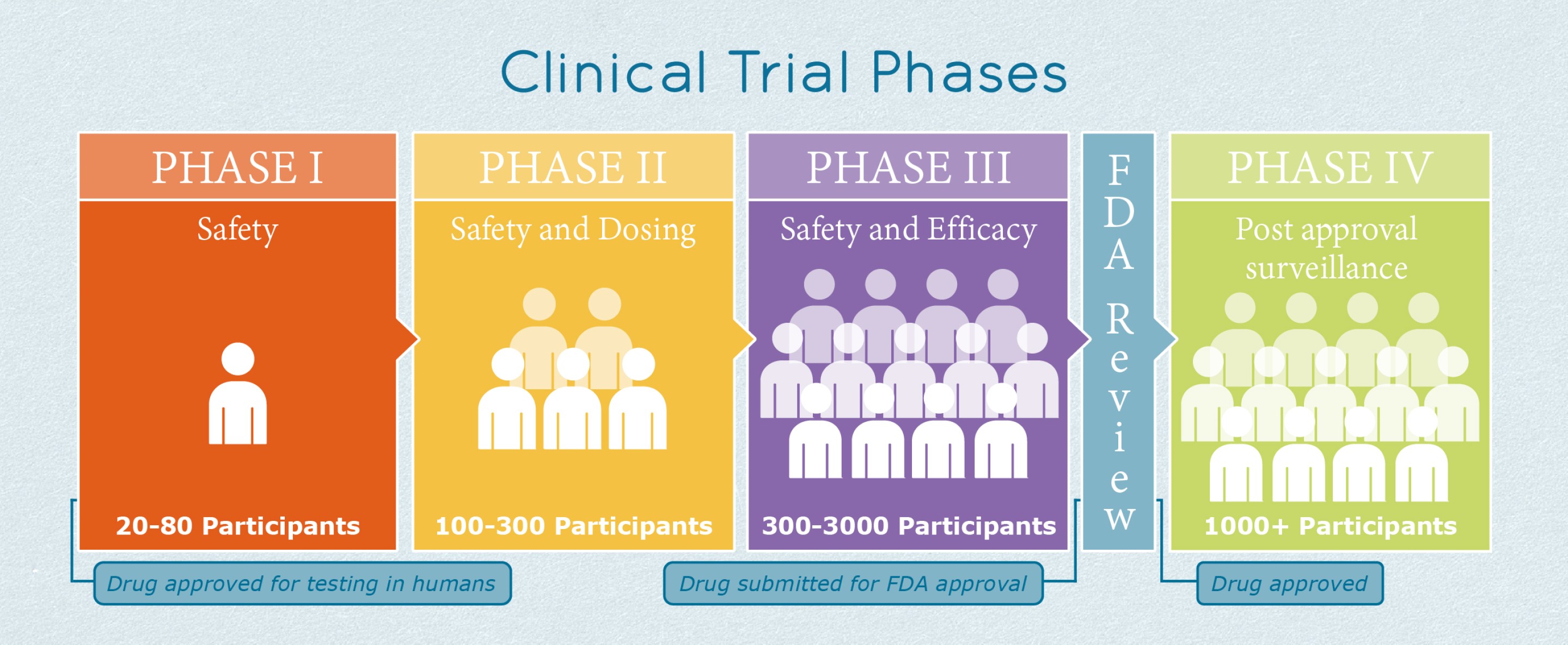

There are three stages of clinical trials that a treatment must pass before it is approved to be prescribed by all doctors in regular offices, clinics, or hospitals.

- Phase 1: The new treatment is tested in 20 to 80 healthy volunteers, or sometimes in people with the condition to be treated. These trials are closely monitored and gather information about how a treatment affects the human body. The goal is to figure out how much of a medication the body can handle and what the side effects are. Researchers also might look at whether the medication seems to be helping, if the study is done in people with the condition. If the medication seems safe and tolerable, it can move to phase 2 trials.

- Phase 2: The new treatment is tested in up to several hundred people with the condition to be treated. Phase 2 studies provide researchers with additional safety data. Early data about whether the drug helps or not is also gathered. Researchers use these data to decide whether a medication should move on to phase 3 studies. Only about one-third of medications that are tested in a phase 2 trial will ever move on to phase 3.

- Phase 3: The new treatment is tested in 300-3,000 people with the condition to be treated, and the study lasts for one to four years. Researchers design Phase 3 studies to show whether or not a medication helps the people to be treated. These studies are known as “pivotal studies” because approval from the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) “pivots” on a successful study. Phase 3 studies also gather a lot of safety data, particularly about side effects that are rarer or may only be seen after taking a medication for months or years.

After a medication or treatment passes phase 3 studies by showing it is helpful and safe, the company can apply for it to become FDA approved. Only about 13% (13 out of 100) of all medications or treatments that start in phase 1 clinical trials eventually become approved.

More information about clinical trials from the FDA can be found here.

Screening Process for Clinical Trials for IPF and PF-ILD Treatment

Before people with IPF or PF-ILD can enroll in a trial, they are “screened” to see if they are eligible. During screening, people who are interested in the trial will answer many questions, and they will need to have their medical records sent to the study investigators. Sometimes, they need to do new scans or other tests as part of the screening process. Eligible patients are usually in a middle ground of lung function. This means not too early in the disease process that any positive effects of medication would be hard to notice, and not too far along in the disease process that medication may not be able to help very much.

To understand the wording used to describe the requirements for people with IPF or PF-ILD to enroll in clinical trials, here are some key screening terms:

- Diagnosis of IPF: The person must have received an official diagnosis of IPF from a physician. Often, the criteria used to diagnose and the time of diagnosis are specified. For example, the trial may require that the person be diagnosed using 2018 Fleischner Society guidelines or 2018 ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT guidelines. The trial may require that this diagnosis have been made (or reconfirmed) within a certain number of years, such as within the past 3 or 5 years.

- Diagnosis of PF-ILD: PF-ILD is a relatively new umbrella term for any interstitial lung disease that does NOT meet the diagnostic criteria for IPF but which causes a rapid accumulation of fibrotic (scar) tissue in the lungs. To be eligible to enroll in the trial, a person with PF-ILD may be required to have evidence of rapid scarring in the lungs over a certain time period. The evidence may come from a series of HRCT scans, FVC testing, or other testing. The time period may be a year, 2 years, or another specific number of years.

- High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scan: HRCT is often done during the screening process to how much scar tissue is in the lungs. The scans show parenchymal fibrosis (scarring), which is overall scarring. In addition, the scan will show what percent of lung tissue is affected by “honeycombing” (the name given when lung tissue looks like many small spaces with walls of scar tissue around the spaces). Higher numbers for parenchymal fibrosis and honeycombing indicate more scarring in the lungs. People with too much scarring or too little scarring are usually not eligible to enroll in IPF studies.

- Forced vital capacity (FVC) test: FVC is the total amount of air that can be forcibly exhaled from the lungs after taking the deepest breath possible. A person with a percent predicted FVC of 100% has all of the lung function that would be predicted for a person of their age and height. A person with a percent predicted FVC of 70% has only 70% of the lung function that would be predicted for a person of their age and height. Lower numbers indicate worse lung function. People with too high or too low FVC are usually not eligible to enroll in IPF studies.

- Forced expiratory volume (FEV1) test: FEV is the amount of air a person can exhale during the first second of a forced breath. As with FVC, a person with a percent predicted FEV1 of 100% has all of the lung function that would be predicted for a person of their age and height. Lower numbers indicate worse lung function. This measurement is often used in a mathematical calculation of FEV1 divided by FVC (FEV1/FVC). This ratio can tell doctors whether a lung disease is obstructive (the outbreath is difficult) or restrictive (the inbreath is difficult). IPF has a restrictive pattern because the lungs are too stiff with scar tissue for people to take an easy breath in.

- Diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO) test: DLCO measures the ability of the lungs to transfer oxygen from inhaled air to the red blood cells in blood vessels. A person with a percent predicted DLCO of 100% has all the ability to transfer oxygen that would be predicted for a person of their age and height. Lower numbers indicate worse lung function. People with too high or too low DLCO are usually not eligible to enroll in IPF studies.

- 6 Minute Walk Distance (6MWD) test: 6MWD is the distance that a person can walk in 6 minutes without help from another person. Mobility aids and supplemental oxygen are allowed if the person usually uses them. People with very limited 6MWD are usually considered too far along in their disease to enroll in IPF studies.