Basics of Interstitial Lung Diseases

The Basics of Interstitial Lung Diseases

Interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) are a group of more than 150 conditions that affect the lungs. In the United States, approximately 81 out of every 100,000 men and 67 out of every 100,000 women have an ILD.1

Although each ILD has unique features, there are common features among them.

What do ILDs have in common?

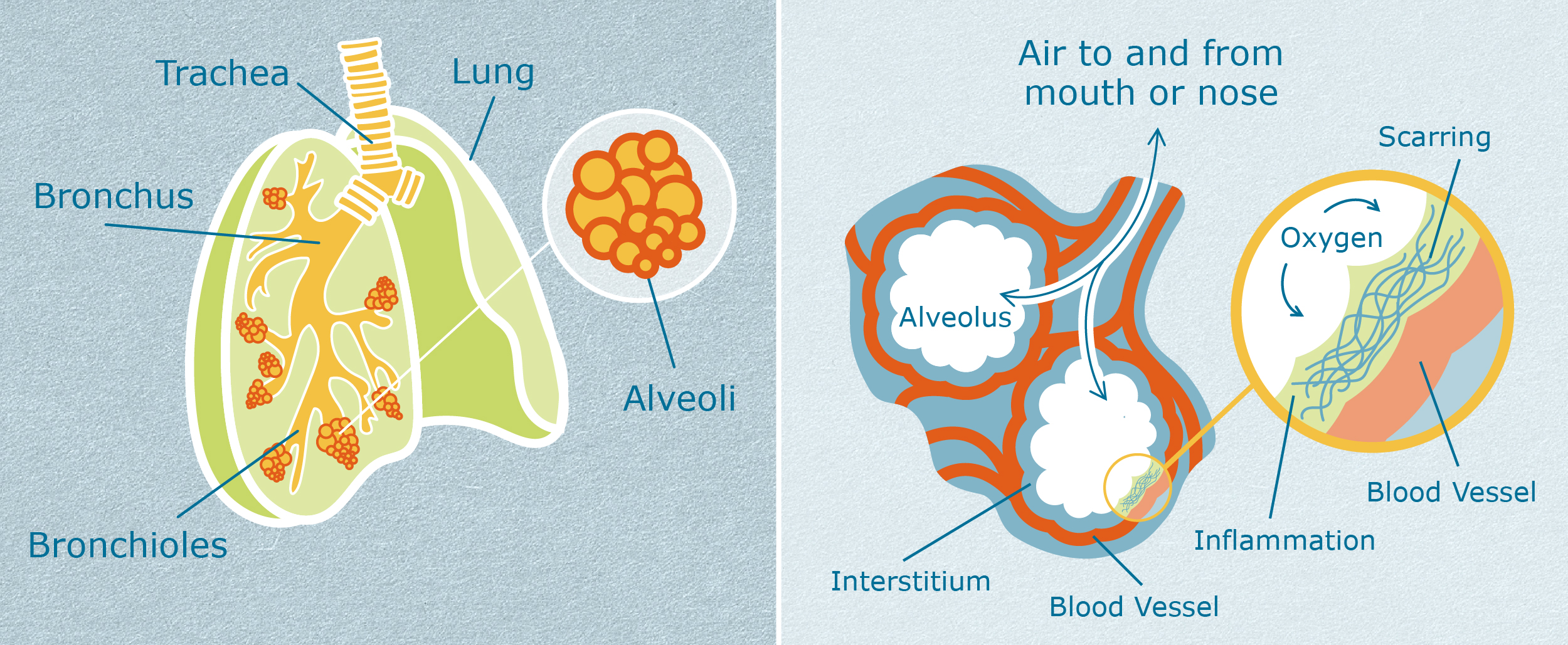

The first common feature of ILDs is that they affect the interstitium (in-ter-STI-she-um) of the lung. To understand more about the function of the interstitium, it can help to visualize how the lungs work.2

During breathing, air enters through the main windpipe (trachea) and flows down branches (bronchi) to the left and right lungs. As the air flows deeper into the lungs, the airways become smaller, with more and more branches (bronchioles). This can be visualized like an upside-down tree, where the trunk is the main windpipe and the branches become smaller and smaller as they move father away from the trunk.

At the end of the smallest branches are clusters of air sacs called alveoli (al-VEE-oh-lie). These look like clusters of grapes. Inside the tiny air sacs, fresh oxygen passes into tiny blood vessels called capillaries (CAP-ill-air-ees), and carbon dioxide passes out of those blood vessels. This movement of oxygen and carbon dioxide is called gas exchange.

The interstitium of the lung is where the gas exchange happens. The interstitium is a very thin layer of lung tissue located in the walls of the alveoli. In healthy lungs, the interstitium is very thin. It cannot be seen on x-ray or CT scan. The air sacs are flexible, and gas exchange happens easily and quickly. For people with ILDs, inflammation or fibrosis (scarring) thickens the interstitium, making the air sacs much less flexible. Gas exchange becomes slow and difficult.

One way to visualize this is to imagine healthy lungs as a balloon. When a person blows into the mouth of the balloon, the rubber walls of the balloon push back a little. Still, the pushback is not so hard that the person cannot blow air in and blow up the balloon. The walls of the balloon move in and out easily as air enters and leaves. Lungs with ILD are like a balloon with very stiff, very thick rubber walls. It takes a great deal of force to push air into the balloon because the walls do not stretch easily. Air does not move in or out easily.

Because of causing stiff lungs, a second common feature among the ILDs is that people with these conditions typically report feeling breathless, especially when they exercise or move around. People with ILDs often also feel very tired (fatigue), even after sleeping or resting. They may also have a dry cough.

What causes ILDs?

Approximately 35% of ILDs have a known cause. The other 65% have an unknown cause.3

ILDs with a known cause include:

- Pneumoconioses—caused by breathing in dust from asbestos, silica, coal, or heavy metals, usually over a long time on the job. Specific names are asbestosis, silicosis, and coal workers’ pneumoconiosis.4

- Extrinsic allergic alveolitis (hypersensitivity pneumonitis)—caused by breathing in animal or vegetable dust. Some people call this condition “farmer’s lung” or “pigeon breeder’s lung”. Common sources of animal or vegetable dust are husks, bark, wood, animal dander, bacteria, fungi, insects and insect fragments, bird droppings, dried urine of rodents, moldy hay/straw/grain, and bird feathers.5

- Iatrogenic ILD—caused by medical treatment, either from medication side effects or radiation treatment side effects. Some types of chemotherapy medications, anti-inflammatory medications, biologic therapies, and heart disease medications can cause ILD in rare cases.6

- Post-infectious ILD—caused by complications from a lung infection. Lung infections can be from fungus, bacteria, parasites, or viruses.

- Autoimmune disease-related ILD—caused by an underlying autoimmune disease, in which the immune system attacks a person’s own body tissues. These include systemic sclerosis, scleroderma, rheumatoid arthritis, dermatomyositis, polymyositis, mixed connective tissue disease, Sjogren's syndrome, sarcoidosis, and inflammatory myositis.7

- Inherited ILD—caused by an underlying genetic disease.8 These include:

- Dyskeratosis congenita

- Neurofibromatosis type 1

- Lymphangioleiomyomatosis

- Tuberous sclerosis complex

- Autosomal dominant hyper IgE syndrome

- Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome

- Gaucher syndrome

- Niemann-Pick disease

- Lysinuric Protein Intolerance

- Surfactant metabolism dysfunction (type 1, type 2, type 3, or type 4)

- Familial adult-onset pulmonary fibrosis

- Familial pulmonary fibrosis associated with telomerase mutations

- Familial pulmonary fibrosis associated with mutations in surfactant protein A

- Familial pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis

ILDs with an unknown cause are called “idiopathic” ILDs. Idiopathic is the medical term for “unknown cause”. These include:

- Sarcoidosis9

- The idiopathic interstitial pneumonias10:

- Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis11

- Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia12

- Respiratory bronchiolitis ILD13

- Desquamative interstitial pneumonia13

- Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia14

- Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia15

- Acute interstitial pneumonia16

- Lymphangioleiomyomatosis17

- Pulmonary Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis/histiocytosis X18

- Eosinophilic pneumonia19

What are the most common ILDs?

The most common ILDs are sarcoidosis, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), autoimmune disease-related ILD, pneumoconiosis, extrinsic allergic alveolitis (hypersensitivity pneumonitis), and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia.3

How are ILDs treated?

The treatment for an ILD depends on whether the cause is known or unknown. When an ILD is caused by breathing in chemicals, animal and vegetable dust, metals, smoke, asbestos, etc., the first and most important step is to avoid or minimize exposure to these substances. If the ILD is caused by exposure to a medication, doctors may switch the person to a different medication.

Treatment for ILDs also depends on whether the ILD is primarily one that causes inflammation in the interstitium, or primarily one that causes fibrosis (scarring) in the interstitium.

An ILD that primarily causes inflammation in the interstititum can be treated by calming the immune system down. Anti-inflammatory drugs, like steroids, or immune suppressant drugs can be used to treat ILDs in this category.

An ILD that primarily causes fibrosis (scarring) in the interstitium can be treated with anti-fibrotic medications. For example, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) causes fibrosis (scarring) and can be treated with nintedanib or pirfenidone. A person with an ILD that primarily causes fibrosis will not be helped by anti-inflammatory drugs or immune suppressant drugs.

What is the prognosis?

The prognosis depends on many factors, including the type of ILD, the age and overall health of the person prior to diagnosis, and how much time went by before the person actually got a correct diagnosis.

Generally, ILDs that cause mostly fibrosis have a worse prognosis than those that mostly cause inflammation. The 5-year survival rate (that is, what percentage of patients are still alive 5 years after the day they were diagnosed) is about 20% in IPF, about 60% in lymphoid interstitial pneumonia, about 80% in nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, about 80% in extrinsic allergic alveolitis, about 90% in sarcoidosis, and nearly 100% in cryptogenic organizing pneumonia.

References and further reading

- Coultas DB, Zumwalt RE, Black WC, Sobonya RE. The epidemiology of interstitial lung diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150(4):967-72.

- National Jewish Health. Interstitial Lung Disease (ILD) Overview. Available at https://www.nationaljewish.org/conditions/interstitial-lung-disease-ild/ild. Updated March 1, 2019.

- European Lung White Book. Interstitial lung diseases. Available at https://www.erswhitebook.org/chapters/interstitial-lung-diseases/. Updated July 2019.

- Cullinan P, Reid P. Pneumoconiosis.Prim Care Respir J. 2013;22(2):249–252.

- Lacasse Y, Cormier Y. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006;1:25.

- Schwaiblmair M, Behr W, Haeckel T, Märkl B, Foerg W, Berghaus T.Drug induced interstitial lung disease. Open Respir Med J. 2012;6:63–74.

- Vij R, Strek ME. Diagnosis and treatment of connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease.Chest. 2013;143(3):814–824.

- Devine MS, Garcia CK. Genetic interstitial lung disease. Clin Chest Med. 2012;33(1):95–110.

- Soto-Gomez N, Peters JI, Nambiar AM. Diagnosis and management of sarcoidosis. Am Fam Physician. 2016;93(10):840-8.

- Travis WD, Costabel U, Hansell DM, et al., ATS/ERS Committee on Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: Update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(6):733-48.

- Sharif R. Overview of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and evidence-based guidelines. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(11 Suppl):S176-S182.

- Belloli EA, Beckford R, Hadley R, Flaherty KR. Idiopathic non-specific interstitial pneumonia. Respirology. 2016;21(2):259-68.

- Margaritopoulos GA, Harari S, Caminati A, Antoniou KM. Smoking-related idiopathic interstitial pneumonia: A review. Respirology. 2016;21(1):57-64.

- Chandra D, Hershberger DM. Cryptogenic Organizing Pneumonia. [Updated 2019 Feb 22]. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.

- Kokosi MA, Nicholson AG, Hansell DM, Wells AU. Rare idiopathic interstitial pneumonias: LIP and PPFE and rare histologic patterns of interstitial pneumonias: AFOP and BPIP. Respirology. 2016;21(4):600-14.

- Bouros D, Nicholson AC, Polychronopoulos V, du Bois RM. Acute interstitial pneumonia. Eur Respir J.2000;15(2):412-8.

- Prizant H, Hammes SR. Minireview: Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM): the "other" steroid-sensitive cancer. Endocrinology. 2016;157(9):3374-83.

- Radzikowska E. Pulmonary Langerhans' cell histiocytosis in adults. Adv Respir Med. 2017;85(5):277-289.

- Marchand E, Cordier JF. Idiopathic chronic eosinophilic pneumonia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006;1:11.